Health problems for Women in Rural Sindh

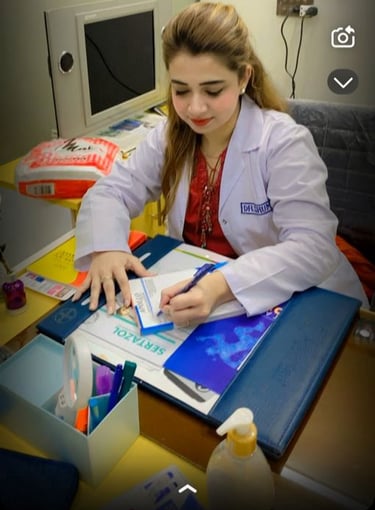

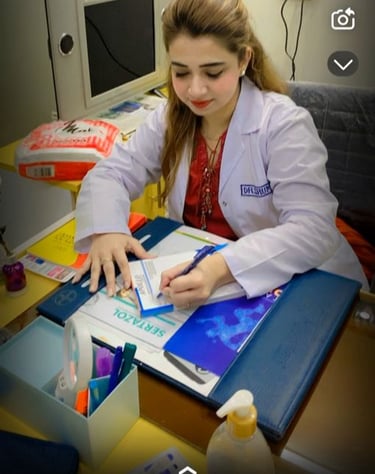

Dr Shumaim Junejo

11/14/20254 min read

Women’s health in rural Sindh remains shaped by a landscape of structural deprivation, cultural constraints, and chronic under investment that collectively deny millions of women the opportunity to live healthy, dignified lives. Any meaningful policy intervention must begin by understanding the dense web of poverty, gender inequality, and institutional weakness that frames their daily reality. In much of rural Sindh, women encounter health challenges from adolescence to old age, with each stage marked by vulnerabilities that are intensified by limited access to services, harmful social norms, and environmental stresses. Maternal health remains one of the most pressing concerns. Rural Sindh continues to face some of the highest maternal mortality ratios in the country, driven by the lack of skilled birth attendants, delays in seeking care, and long distances to functional health facilities. Many basic health units remain understaffed, without midwives, ultrasound services, emergency transport, or essential medicines. As a result, women rely heavily on untrained traditional birth attendants, who lack the capacity to identify complications early or facilitate timely referrals. The three delays—delaying the decision to seek care, delaying transport, and delaying treatment—combine to turn preventable complications into fatal outcomes. Malnutrition is another severe and persistent crisis.

A staggering proportion of women in rural Sindh suffer from anemia, micronutrient deficiencies, and low body mass index, which in turn contributes to low-birth-weight babies and intergenerational cycles of poor health. Food insecurity, limited agency in household decisions, and the cultural normalization of women eating last exacerbate this long-term deprivation. Adolescent girls often enter pregnancy while undernourished and physically immature, further heightening risks of obstructed labor, stillbirth, and long-term reproductive complications. Reproductive health remains constrained by lack of knowledge, restrictive gender norms, and minimal access to family planning services. Contraceptive prevalence remains significantly lower in rural regions, partly due to supply shortages, weak community outreach, and the stigma surrounding discussions of reproductive autonomy. Women frequently have little control over decisions related to birth spacing, and many are compelled into repeated pregnancies that endanger their health. For those requiring specialized care—such as screening for breast or cervical cancer—services are almost entirely absent at the rural level. Preventive care, which should be the foundation of a functional system, is rarely available in any consistent or quality-assured manner. Waterborne diseases, poor sanitation, and unsafe drinking water contribute to chronic ill health, especially gastrointestinal infections and hepatitis, which disproportionately harm women who spend more time managing household tasks involving water. Rural Sindh has some of the lowest sanitation indicators in the province, with open defecation and contaminated water sources still prevalent in several districts. Flooding in recent years has worsened water contamination, increased vector-borne diseases, and destroyed health infrastructure, further marginalizing women who already faced obstacles to accessing care. The burden of mental health, though rarely acknowledged, is substantial. Early marriages, domestic violence, financial dependence, and restricted mobility create a climate of psychological stress that remains largely invisible in policy frameworks. Women’s mental distress manifests in chronic fatigue, depression, and anxiety, yet the health system neither identifies nor treats these conditions adequately. Stigma surrounding mental illness prevents open conversation, and rural health workers are rarely trained to provide basic mental health support. Health services that do exist often fail due to governance failures and poor accountability. Many facilities suffer chronic absenteeism, mismanagement of funds, and shortages of female staff, which discourages women from seeking care. Transportation remains one of the most practical barriers. In vast stretches of Tharparkar, Khairpur, Dadu, and other districts, women must travel long distances—often over rough terrain—to reach even a basic facility. Cultural norms restricting mobility without a male escort further limit access, delaying treatment until complications become severe. To transform women’s health outcomes in rural Sindh, policies must place women at the center of decision-making rather than treating them as passive recipients of services. Strengthening primary healthcare through fully functional, well-staffed, and continuously supplied units is essential. Midwives and lady health workers must be trained, retained, and equipped with modern tools, ensuring consistent presence in villages rather than intermittent or symbolic coverage. Community-based awareness programs led by female health educators can shift harmful norms around family planning, nutrition, and antenatal care, especially when men are included in dialogue. Emergency obstetric care must be expanded with reliable referral networks, ambulance services, and district-level hospitals capable of handling complications at any hour. Long-term improvement requires investment in nutrition programs that address poverty, food insecurity, and adolescent health simultaneously. School-based health interventions, micro-nutrition supplements, and social protection for pregnant women can significantly reduce risks. Water and sanitation development must be integrated with health planning rather than treated as a separate sector. Ensuring safe drinking water, building latrines, and monitoring water quality are as important as providing medical services. Mental health support should be introduced through training of community health workers and confidential counseling spaces within existing facilities. Above all, women’s health must be embedded in a broader agenda of gender equality, education, and economic empowerment. When women’s autonomy, mobility, and literacy improve, so do their health outcomes. A policy framework that combines medical access with social transformation is the only sustainable path to safeguarding the well being of rural Sindh’s women.

Dr. Shumaim Junejo has served as YEW's regional coordinator from Hyderabad, Sindh. She did her MBBS from Liaquat University of Medical and Health Sciences. She serves as a 17 grade Women Medical officer in Government of Sindh. She has extensively worked in covid and flood campaigns in Sindh.